- Код статьи

- S032103910017253-1-1

- DOI

- 10.31857/S032103910017253-1

- Тип публикации

- Статья

- Статус публикации

- Опубликовано

- Авторы

- Том/ Выпуск

- Том 82 / Выпуск 3

- Страницы

- 597-622

- Аннотация

Since the discovery at Garni (Armenia) in 1945 of a Greek inscription mentioning a king Tiridates (Trdat), there has been an ongoing debate on the identification of this king. On the basis of paleography and content, most scholars have preferred to date the document to the first-century CE reign of Tiridates I, despite what seemed to be a suggestive indication from the historian of Armenia Moses Khorenatsi that Tiridates the Great, in the early fourth century CE, had dedicated a Greek inscription in memory of his sister at Garni. This study attributes the inscription to the reign of Tiridates the Great, although it shows also that this text cannot be the one referred to by Moses Khorenatsi. This reattribution is of special importance for the early history of Armenia. It paves the way for a new analysis of the reign of the king who initiated the Christianization of the country. Our next article, in a forthcoming issue, will offer a new and full critical edition of the inscription, comparing it with prior reconstructions.

- Ключевые слова

- Armenia, Garni, Tiridates the Great, Christianization, Agathangelos, Moses Khorenatsi

- Дата публикации

- 26.09.2022

- Год выхода

- 2022

- Всего подписок

- 3

- Всего просмотров

- 130

Garni is a site at the foot of a mountain ridge, about 25 km east of present-day Yerevan. Located on a bluff overlooking the Azat River, the place was also naturally easy to defend1. From the earliest times until the medieval period, it had a special importance for the history of Armenia. Begun in the early twentieth century and restarted after the Second World War, excavations at Garni have revealed the existence of buildings of various periods, especially of a temple built in the early Roman imperial period and of fortification walls of various periods2. It is at the fortress of Garni (castellum Gorneas), in 51 CE, that Tacitus (XII. 45. 3) locates a tragic episode of the war between Mithridates as king of Armenia and his nephew Rhadamistus, who wanted to succeed him. Mithridates was besieged at Garni, forced to capitulate, and executed (Tac. XII. 44–47).

In 1945, a sensational discovery was made by chance, that of a Greek inscription mentioning a king Tiridates as king of Greater Armenia (Armenia Maior). This discovery was followed by that of three more inscriptions in various languages and scripts and from various periods. The earliest one, in Urartian and cuneiform characters, is a dedication from King Argišti I, in the first half of the eighth century BCE, which mentions, line 3, that the king “conquered the city of Ḫi[x]rinia”3. An Aramaic inscription of the second or third century CE mentions a king of Armenia (his name is mutilated), son of a king Vologases4. The latest one, dated to 1291 CE, was engraved in Armenian language and characters on the entrance wall of the temple by Princess Khoshak of Garni5. These inscriptions suffice to illustrate the significance of the site of Garni in the longue durée history of Armenia.

4. Perikhanyan 1964; Russell 1987, 118–119; Movsisyan 2006, 205.

5. Arakelyan 1951–1976, III, 45.

The Greek inscription has understandably attracted much attention. It has been published and commented upon many times in articles and monographs. Two books, and a large part of another one, have been dedicated to it6. It is also easy to understand why it appears regularly in most publications dedicated to the history of Armenia7. Since its discovery, the date and meaning of the inscription have been hotly debated. The inscription mentions a king Tiridates. But several Arsakid kings of Armenia are known to have born this name: Tiridates I, who, with some interruptions, reigned over Armenia from 53 to perhaps 75 CE; Tiridates II seemingly between 216/7 and 252; and Tiridates III between 298 and ca. 3308.

7. It is unnecessary to give here the long list of these books, articles, and websites.

8. Bivar 1983, 79–85, on the Arsakid kings of Armenia. The dates of reign of these kings have been the object of intense debate. We follow here Toumanoff 1986 for the dates of reign of Tiridates I and Tiridates II, but while accepting Toumanoff’s date of 298 for the accession to power of Tiridates the Great, we keep for him the traditional regnal number, III, not IV: see Weber 2016.

In this respect, it may seem that Moses Khorenatsi, the famous historian of ancient Armenia, provides a crucial indication. A propos King Tiridates III “the Great”, the king under whom Armenia converted to Christianity, he mentions: “About that time [after the council of Nicaea] Trdat completed the construction of the fortress of Garni in hard and dressed blocks of stone cemented with iron [clamps] and lead. Inside, for his sister Khosrovidukht, he built a summer palace with towers and wonderful carvings in high relief. And he composed in her memory an inscription in the Greek script”9.

The connection with the inscription found at Garni may thus seem obvious. However, only a minority among the specialists who have edited or commented upon this text has retained the view that the king mentioned in the inscription was Tiridates III10. A significant majority, starting from its first editor, has preferred to see here a reference to Tiridates I, the first king of the Arsakid / Aršakuni dynasty, the family which ruled over Armenia until 428 CE11. At the compromise of Rhandeia, in 63 CE, Rome acknowledged the fact that Armenia would be ruled by a member of the Parthian royal family, provided this king officially accepted to owe his crown to the Roman Emperor. This is how Tiridates I, who had already reigned over the country, was definitively acknowledged king of Armenia. The conclusion that this inscription should be referred to King Tiridates I has also been followed by general historians of Armenia12. Finally, this is the date that is now found in many papers and online publications for the general public referring to this text.

11. Lisitsyan 1945a; 1945b; Abramyan 1947; Trever 1949; 1953; Moretti 1955; Sarkisyan 1960, 67–69; Bartikyan 1965; Krkyasharyan 1965; Muradyan 1981; Vinogradov 1990; Ananyan 1994; Kettenhofen 1995, 113–120. The text has found its place in the collection of inscriptions of the Flavian period by McCrumm, Woodhead 1961, 72, no. 238. For the early history of Amenia and the Aršakuni dynasty, see Garsoïan 1997a; 1997b.

12. Russell 1987, 269–281; Nersessian 2001, 103; Olbrycht 2016, 101; Mastrocinque 2017, 198–203.

As mentioned previously, the inscription has been edited and commented upon many times. Yet, despite its crucial significance as a testimony of the ancient history of Armenia, it is fair to say at this time that no consensus has been reached on the establishment of the text. More than seventy-five years after its discovery, the various editions of the inscription still present essentially different versions, the last ones not bringing the final word. This shows that the reading and understanding of the text have never stabilized.

The first reason for this situation is the fact that the right part of the inscription is missing, which has given rise to very different solutions of restoration. However, even the establishment of the preserved part has not been an object of consensus. The second reason that explains the extreme differences between the editions is a division of the scholarship between schools that did not have full opportunity to collaborate with each other. Three schools of scholars, the Armenian one, the Russian one and the Western one, have studied this text. The Russian school and the Armenian were of course intimately linked, but each retained its own traditions and ideas. For a long period, with few exceptions, Western scholars had little direct access to the studies of Armenian scholars, and limited access to those of Russian ones. Similarly, Armenian scholars had minimal access to Western scholarship or to the works of their Russian colleagues if they were published in the West. In the past, a critical analysis of the previous states of the scholarship on this document was hardly possible. The more open world in which we lived until recently allowed us to reassemble these membra disiecta.

Starting for the first time from a complete lemma of the various editions, this study offers a critical edition of the inscription, providing both a new text and a new translation. On several points it provides solutions that had never been envisaged. And on some others, it brings back to our attention, under a new form, some arguments that we believe have been overlooked, thus emphasizing the significant work done by previous generations of scholars who investigated this text. It is clear also that we now benefit from research tools that previous generations lacked and that allow us to quickly test our hypotheses, a luxury completely unknown to the research of the past.

Our strategy of edition will be the following: after presenting the lemma of the inscription and its divergent readings, we present the stone and the script, layout and spelling of the inscription, before analyzing in their context the names mentioned in the text. This allows us to draw a first conclusion on the chronology of the document. Then we address the question of the word Helios at the beginning of the text, which has been a crux in the interpretation of the document. Then follows a line-by-line critical commentary, which finally enables us to propose a new text and translation, as well as a short conclusion on the signification of the text.

1. THE STONE AND ITS INSCRIPTION: PREVIOUS EDITIONS AND INTERPRETATIONS

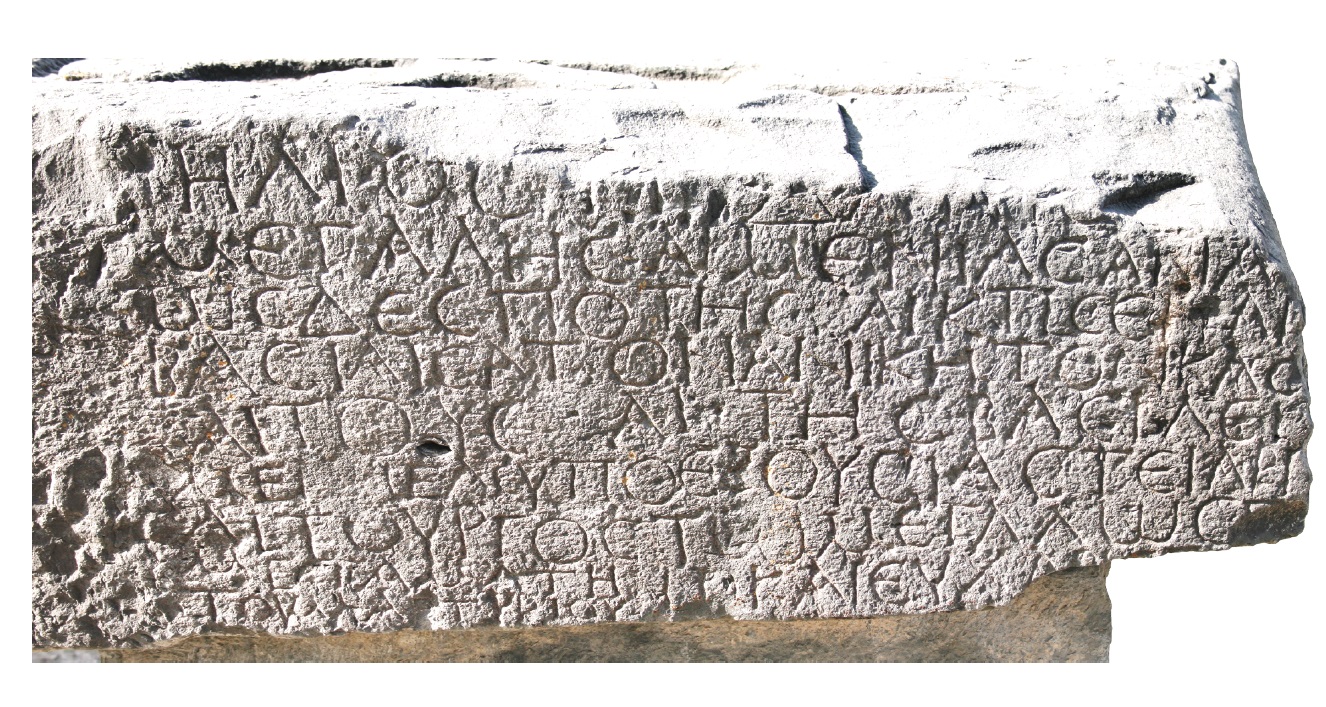

The stone (fig. 1), in the local black basalt to be found on the very site of Garni, was discovered in 1945 by the painter Martiros S. Saryan and by Tsolak Davtyan in the cemetery of the village13. On one of its broad surfaces (originally the top of the block) it bears a large cross, which shows that the stone was reused as a khachkar, the characteristic memorial stele of Christian Armenian cemeteries. On the left side of the khachkar, on a side that would originally have been the face of the block, we find an inscription in Greek letters. When one faces the inscription, the right part of the stone is missing, and with it the right part of the text (the block narrows toward that side, possibly because it was carved to help the khachkar stand in place). The upper rim of the face with the inscription is also damaged to the right, leaving legible only the lower parts of the letters of the name of a King Tiridates. The lower right corner of the block is also missing, and with it the final part of the inscription.

On the side that bears the inscription, the right part of the stone, which bears the text, was carefully dressed, but the left part was left undressed. The top surface (now with the khachkar) still presents three cramp holes, one to the left side, two to the rear. There was certainly a fourth one in the missing part of the block to the right. This massive block does not come from the temple found within the fortress walls.14 It was inserted in a masonry wall, in all likelihood from the fortification, perhaps (but this is not certain) as a lintel.15

15. See Vinogradov 1990 for the suggestion that the stone was originally a lintel.

Fig. 1. The block bearing the Garni Greek inscription. Photo by E. Fagan

Dimensions (in cm): Stone L 165, W 80, T 50. Cramp holes: 3x5, depth 4. Letters: 5–5.5, slightly bigger in the first line, and letters of smaller size, 3 cm, in the lower left part of the inscription. One interpunction in the shape of a colon line 3, two in the shape of dots in the middle of line 5.

Editions and textual commentaries: Lisitsyan 1945a; 1945b; Manandyan 1946; Abramyan 1947; Trever 1949; Manandyan 1951; Trever 1953; Moretti 1955 (Robert J., Robert L. 1956, no. 345; SEG 15 836; McCrum, Woodhead 1961, 72, no. 238); Sarkisyan 1956; Elnitsky 1958 (SEG 20 110); Sarkisyan 1960, 67–69; Bartikyan 1965; Krkyasharyan 1965; Feydit 1969 (Chaumont 1969, 177–182); Muradyan 1981; Movsisyan 2006, 237–238; Vinogradov 1990, 559–560, no. 605 (SEG 40 1315; Canali DeRossi 2004, no. 17); Ananyan 1994; Kettenhofen 1995, 113–120 (SEG 45 1873); Ferretti and Magarditchian 202016.

This long list of editions has produced texts that present exceptionally sharp differences from one another. In this series, those of Trever 1949 and 1953, Moretti 1955 and Vinogradov 1990 distinguish themselves by the quality of their readings, although many of the other editions also make important observations. However, the condition of the stone and inscription has meant that scholars have found it difficult to resolve all questions, which opened the gate to new speculations and editions, with varying results. As examples of these divergent interpretations, here are the two editions and translations proposed by Trever in 1953 and Vinogradov in 1990.

Trever 1953, 187:

Ἥλιος Τιριδάτης [ὁ μέγας] | Μεγάλης Ἀρμενίας ἀνά[κτωρ]. | ὡς δεσπότης αἴκτισεν ἀγ̣[άρακον] | βασιλίσ(σ)ᾳ τὸν ἀνίκητον κάσ[τρον] |5 αἴτους αιʹ τῆς βασιλεί[ας] | Μεννέας ὑπὸ ἐξουσίας τειαρί[ου] | λιτουργὸς τῷ μεγάλῳ σπ̣[αραπέτ]|ῳ καὶ εὐχάρι[στος | μετὰ Ματηίου τοῦ μάρτυρ[ος].

Helios! Tiridates the Great, Sovereign of Greater Armenia. When the ruler built an agarak for the queen [and] this impregnable fortress in the eleventh year of his reign, Menneas, with the permission of the ter, [as] liturgist of the great sparapet, [as a token of] gratitude, in the presence of Mateis the witness, [repaid his debt]17.

Vinogradov 1990:

Ἥλιος Τιριδάτης [ὁ μέγας βασιλεὺς] | μεγάλης Ἀρμενίας ἀνα[χθείσης τῆς πόλε]|ως δεσπότης αἴκτισεν αἱ[αυτοῦ ἀδελφῇ] | βασιλίσᾳ τὸν ἀνίκητον κάσ[τελλον τοῦτον?] |5 αἴτους αιʹ τῆς βασιλεί[ας ἐπὶ σωτηρίᾳ vel sim.]. | Μεννέας ὑπὸ ἐξουσίας τειαρι[φόρου κυρίου?] | λιτουργὸς τῷ μεγάλῳ σε[μνῷ θεῷ Ἡλίῳ vel sim.] | μετὰ ματη|τοῦ Μαρτυρίου ᾧ καὶ εὐχαριστ̣[εῖ].

I, Helios Tiridates, the great king of Greater Armenia, lord of this rebuilt city, have built for my sister-queen this invincible fortress, in the eleventh year of my reign, for the safeguard (?). Menneas the stonecutter, through the goodwill of the master who carries the tiara, has dedicated to the great holy god (Helios?), to whom he also gives thanks with his pupil Martyrios18.

These two examples suffice to illustrate the breadth of divergences between the various editions.

2. SCRIPT, LAYOUT AND SPELLING

2.1. Layout and script

The layout of the text of the Garni inscription (fig. 2) is not regular. The lines are not aligned with the horizontal axis. The letter height, width and spacing are also irregular. The letters are slightly taller in the first line and they may be smaller afterwards, but with no regular pattern. The letters have small decorative serifs under the form of a short dash. All (or almost all, see below) the letters that may possibly have a lunate shape present this characteristic. This is the case with epsilon, sigma, mu, and omega (Ⲉ, Ϲ, Ⲙ, Ⲱ). The alphas present a broken bar and a right stroke that at the top is slightly longer and extends at the top of the letter. The betas are narrow and their loops are irregularly shaped. The deltas present the same characteristic as the alphas, with a right stroke slightly protruding at the top of the letter. The iotas are not always vertical (sometimes seriously slanting, like line 5, second letter). The shapes of the four kappas vary significantly from one to the other. The mus have all a deeply incurved shape, and the bars are reduced to two small dashes at the foot of the letter. The skew stroke of the nus attaches itself not at the extremity but a short distance of the left and right stroke. The xi has a cursive shape. The loop of the omicrons has the full diameter of the line and sometimes even beyond it. The pis are large and the upper bar slightly protrudes on both sides. The loop of the rhos is small and attaches itself at around one third of the vertical stroke. The omega has a fully developed double-U shape19.

As for the layout, Trever already observed that from line 6, we have so to speak two texts in parallel. Line 6, the first word, ⲘEΝΝEΑϹ, is written in letters smaller than the rest of the line. Line 7, the letters of ΛΙΤΟΥΡΓΟϹ are only slightly smaller than the rest of the line and they are not in the continuity with, but slanting towards it. As for what corresponds to line 8 of the main text, we have two lines, 8 and 9, in smaller characters, ⲘEΤΑⲘΑΤΗ | ΤΟΥⲘΑΡΤΥΡΙΟΥ. In this portion of text, a special case must be made for the epsilons at the beginning of lines 6 and 8. Twice line 6 for ⲘΕΝΝΕΑϹ and once line 8 for ⲘΕΤΑ, the epsilons are square-shaped, which is all the more curious that both in lines 6 and 8 we have lunate sigmas in the rest of the line. It seems that the engraver (if there was indeed only one for the whole text) deliberately switched to a different style of letters, as if he wanted to send a warning on the way these lines were to be considered. It is thus an unavoidable conclusion that, to the left, the portion of text ⲘΕΝΝΕΑϹ | ΛΙΤΟΥΡΓΟϹ | ⲘΕΤΑⲘΑΤΗ | ΤΟΥⲘΑΡΤΥΡΙΟΥ must not be read in continuity with the rest of the lines but forms a distinct unit, exactly a first column, whilst, to the right, the rest of the lines should be read as a second column.

Fig. 2. The Garni Greek inscription. Photo by E. Fagan

Trever (1953) concluded that the left column (in our edition, see below, lines 6–9) was written by a different hand from that of the second one (in our edition lines 10–12), which in fact is not correct (see below for a different explanation), but her remark shows that she recognized that this portion of text had a different status20. Curiously, in contradiction with this observation, she translated the lines of the first column in continuity with those of the second one21. Even though he did not analyze the matter in detail, Moretti (1955) also saw that this portion of text was a distinct unit22. A few other scholars only (Krkyasharyan in 1965 and Muradyan in 1981) also recognized the existence of a separate block of text, although they did not draw significant conclusions from this observation. For now, it suffices to observe that the layout of the text may legitimately appear confusing to the modern reader. But the letters of ancient inscriptions were commonly painted. If we assume that the letters of the first column were painted in a color different from the rest of the text, the inscription would have been easily readable.

21. Trever 1953, 187.

22. Moretti 1955, 42.

One had to wait Vinogradov (1990) to fully understand that “column 1” had been written in the same time as the rest of the text and for this reason his translation is correct (his translation of lines 8–9 should follow immediately that of lines 6–7, but this has no consequence for the meaning of the text). There will remain to make sense of the apparently strange choice to introduce this first column, written in characters distinctly smaller and with a script (for the epsilons) partly different of the rest of the text.

The script of the inscription has been used to provide justifications for very different suggestions of dating, and the question must be reexamined in full by putting the stone in its context. The strategy of Trever was to retain as parallels the inscriptions of the Caucasus region only. Ours will start from the broader picture of the Greek inscriptions of the eastern Mediterranean and Iran, before coming back to the inscriptions of the Caucasus.

As observed, except for some epsilons (see above), the Garni inscription presents systematically lunate shapes for epsilon, sigma, mu, and omega. Lunate letter shapes appear in some inscriptions as early as the Hellenistic period. Lunate or curved letter shapes were used with an increasing frequency in the imperial period, but each region had its own evolution. In Iran, they are to be found systematically in stone inscriptions starting in the early first century CE23. In Syria they appear earlier than, for instance, in Mainland Greece and in the Black Sea regions24. But all over the imperial period until the fourth century (and later), it was always possible to use inscriptions with “traditional” shapes of epsilon, sigma, mu, and omega25.

24. For Syria, the selection of inscriptions provided by Choix Syrie, which covers a very long chronological period and offers many precisely dated inscriptions, shows the quick dominance of lunate shapes, but non-lunate letter shapes still appear under Domitian, see no. 1, and under Trajan, no. 2.

25. A good case is provided by the various Greek versions of the Maximum edict of 301 CE. A majority of them are then written with lunate shape letters, but some of them still make use of “traditional” or mixed letter shapes (Edictum Diocletiani Giacchero, vol. 2: traditional shapes in Thebes, no. 90, pl. LIV; Carystos no. 16, pl. LXX and LXXI; Tamynaion [Euboia] no. 115, pl. LXXII; Thespis no. 130, pl. LXXVI; Tegea, no. 57, pl. LXXIX). In a period where lunate shapes were now used for a majority of inscriptions, a dedication to Diocletian from Tomis (I. Tomis 111), dated to 284–286 CE, used Ε, Μ, square sigmas and a square W shaped omega. The examples could be multiplied.

If we turn to the inscriptions from the Caucasus, it is the dossier of Iberia that offers the richest comparandum. Discussing the case of the Greek-Aramaic bilingual funerary inscription of Serapeitis, with its lunate or curved shapes for epsilon, sigma, omega and mu, Trever does not identify for it a conclusive first century date, allowing that it may also belong to the early second century CE, but she goes on to use it to date the Garni inscription to the first century26. However, when we compare the Serapeitis inscription to the Vespasianic stele of 75 CE from Armazi, we observe in the latter the traditional, non-lunate shapes Ε, Σ, Ω, Μ, which does not fit with Trever’s chronological argument27.

27. I.Georgien3 229 (fac-sim., photo in Braund 1994, 68, fig. 17). Trever 1953, 201, who dated the Garni inscription from 77 CE, two years after the Vespasian inscription from Armazi, did not comment on the lettering discrepancy.

Admittedly, the point is not to quibble on the chronology of individual inscriptions, and it is the case that whether on stone, gems or silverware, from perhaps the end of the first century CE or the beginning of the second century to the beginning of the fourth century, Greek inscriptions from Iberia present regularly lunate or curved shapes, Ⲉ, Ϲ, Ⲱ, Ⲙ (or the square W shape for the omega), sometimes with remnant non-lunate shapes28. It remains that, on the basis of the letter shapes, the comparison with the inscription of Iberia does not force us to conclude that the Garni inscription should be dated to the first century, and may even invite the opposite conclusion.

The dossier of the Greek inscriptions of Аrmenia from the imperial period is more limited but leads to similar conclusions about the possible breadth of dating. Two stone inscriptions from the late second century present lunate shapes29. The same characteristic can be observed on the inscription on a silver cup offered by King Pakoros (second half of the second century CE, who might be the king of Armenia of that name)30. Two inscriptions deserve particular attention.

30. I.Estremo Oriente 21 (fac. sim. Trever 1953, 253, fig. 35). See also below and n. 37 and 84–85 for that inscription.

The first one is the inscription from the bath mosaic from Garni, which has mixed letter shapes: “traditional” epsilons and mus, but square sigmas and omegas. On the basis of stylistic arguments, of the pagan mythologic themes and nudities, and of the letter shapes as compared to those of the mosaics of Antioch, B.N. Arakelyan dated it to the end of the third or beginning of the fourth century, before the conversion of the kingdom to Christianity31. Whatever its exact date, a late imperial chronology is indeed certain.

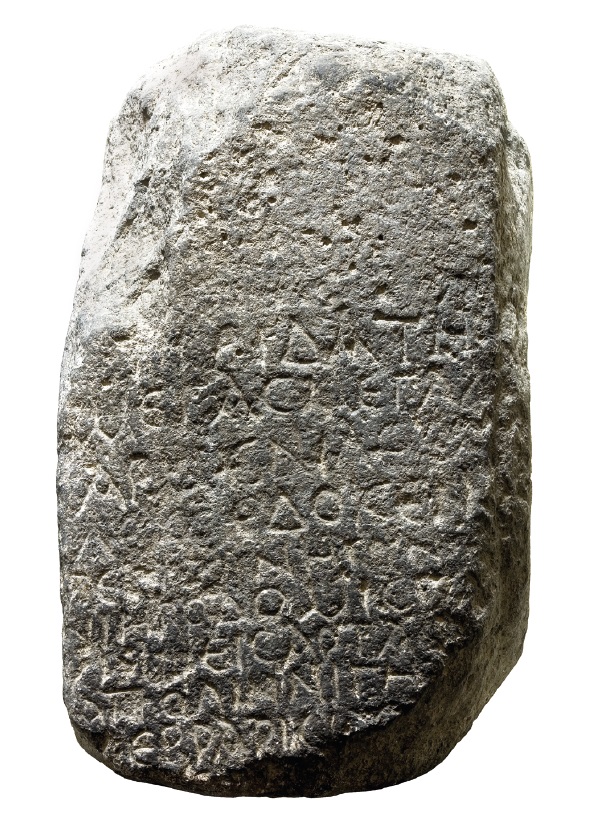

Fig. 3. The Aparan inscription. Photo courtesy of the History Museum of Armenia

The second inscription that demands attention is the royal donation from Aparan (about 55 km north of Yerevan), made by a king Tiridates (fig. 3). It begins with the titulature Τιριδάτης [ὁ] | Μέγας μεγάλ[ης] | Ἀρμενίας βα[σι]|λεύς (ll. 1–4), for which the parallel with the Garni inscription, though with some differences, is striking32. The script of the two inscriptions is also closely akin (even the broken bar of the alpha is found in both documents). The similarity in their layout makes the parallel between the two inscriptions even more striking: it is characterized by the absence of regularity, irregular letter sizes and poor line alignment with the horizontal axis.

Clearly, the Garni and Aparan inscriptions cannot be separated by a large chronological gap but have a good chance to have been engraved under one and the same king Tiridates, though we must still determine which one. Rostovtzeff argued in favor of a late chronology for the Aparan inscription (the Garni inscription had not yet been discovered)33. Acknowledging the resemblance in their scripts, Moretti (1955), although after hesitating for a date under Tiridates II, and Vinogradov (1990) dated both texts to the first century CE, whilst Elnitsky (1958) dated them to the turn of the third and fourth century. Although noting the similarity between the two inscriptions, Trever dated the Garni one to 77 CE and the Aparan one to 217–28234. Conversely, Chaumont dated the Garni inscription to the reign of Tiridates III, but the Aparan one to the first century35. Canali DeRossi dated the Aparan inscription (following Vinogradov) to the first century and the Garni one to 298, quoting for this date Kettenhofen 1995, but who in fact dated it to the first century CE: this difference in dating is thus based on a material error and for this reason can be discarded36.

34. Trever 1953, 271–283, esp. p. 282 for the date. Ibid. 274–277, she adduced a contrast between the script of the Aparan inscription and that of “Tigranocerta” (in fact Martyropolis / Silvan), which she herself republished ibid. 283–288 (= I.Estremo Oriente 53, with lemma at the date), with its characteristic ligatures and abbreviations, and which she dated to the second half of the fourth century. But this date is impossible to accept. Mango 1985 (SEG 35 1475) redated the text to 591 CE. Niehoff-Panagiotidis (2019, 660), on the basis of verisimilitude arguments, proposed a date in the 410s, which however fails to convince for the author does not analyze the script of the inscription. A significantly later date is most likely. The newly found mosaic inscription from Jerusalem (Borschel-Dan 2017), of the sixth century (under Justinian), provides a good benchmark for a comparison. For the history of Sophene in Antiquity, see Marciak 2014.

35. Chaumont 1976, with 185–188, for the Aparan inscription, dated to the first century CE on the basis of her acceptance to read in this text the name of a Rhodomis[tos], who would be the son of the Iberian king Rhadamistos, the besieger of his uncle at Garni. But she herself notes that the name is present in the kingdom of Bosporos. Indeed, the Iranian name Ῥαδάμειστος is to be found at Tanais (CIRB 1262, l. 17, 2nd c. CE; possibly also, with restoration, 1277, l. 27, 3rd c. CE) and at Theodosia (CIRB 947 A, l. 6, 3rd c. CE); see also the index of CIRB, s.v. Ῥαδάμασις, Ραδάμιος (?) and Ῥαδαμόφουρτος (many other Iranian names are attested in the Pontic region). Thefefore, there is no particular reason to link the “Rhodomis[tos]” of the Aparan inscription (if the reading is correct) to Tacitus’ Rhadamistos.

36. I.Estremo Oriente 17–18. The mistake was already in SEG 45 1873. In reality, Kettenhofen 1995, 120, concluded: «Ich meine, daß der Ersteditor der Inschrift, Lisicjan, mit der Datierung ins 1. Jh. n. Chr. schon das Richtige gesehen hat».

The Iberian inscriptions of the late first or second centuries as well as the inscription of King Pakoros on a silver cup of the second half of the second century are remarkable for the elegance and classic regularity of their layout and engraving37. The question is to determine what to do with the rather sloppy layout of both the Garni and Aparan inscriptions. It is tempting to consider that a chronological gap is here the decisive factor of differentiation. Even if this is certainly not an absolute rule, late imperial inscriptions tend to be increasingly characterized by the sloppiness of their engraving, which can be observed for instance in several copies of Diocletian’s Maximum Edict or in milliaria of the period38. For this reason, the balance shifts heavily for a late date, in the late third or beginning of the fourth century, for the Garni and Aparan inscription, although admittedly this does not yet provide a final proof for a late chronology of these documents.

38. For the Maximum Edict, see Edictum Diocletiani Giacchero. For the milliaria, see French 2012–2016. A well-illustrated series of five milestones from Sekköy, in Caria, bearing a total of 11 texts and covering the period from 201 CE (under Septimius Severus) to c. 340–350 CE (under Constantius II and Constans) illustrates perfectly the differences in the layout and engraving over time (see Varinlioğlu, French 1991; 1992 = I.Carie hautes terres 93–97 = French 2012–2016 fasc. 3.5 Asia, pp. 214–220, no. 118).

2.2. Spelling

The text of the Garni inscription presents a series of spellings that diverge from the standard ones: l. 3, αἴκτισεν for ἔκτισεν, l. 5, αἴτους for ἔτους, which in turn, l. 5, helps to vindicate the restoration αἱ[αυτῷ] (on which see below). The confusion αι for ε and vice versa, based on an identical pronunciation /e/, becomes increasingly frequent from the mid-imperial period onwards. As for λιτουργός for λιθουργός, l. 7, and ματητοῦ for μαθητοῦ, ll. 8–9, Moretti39 was the first to interpret correctly the former, and Elnitsky40 followed by Vinogradov (1990) rendered appropriately both words: the unaspirated occlusive replaced the aspirated corresponding one. Similarly, we have ἔδοκε for ἔδωκε and [Φ]εβράρις for Φεβράριoς in the Aparan inscription, as well as Ἐγιαλός for Αἰγιαλός and Πιθώ for Πειθώ (to which should be added ἠργασάμεθα for εἰργασάμεθα) in the Garni mosaic41.

40. Elnitsky 1958, 146–148.

41. Arakelyan 1956, 154, saw in the forms Ἐγιαλός and Πιθώ a clue for a late dating of the Garni mosaic. Elnitsky 1958 also noted the simplification Θάλασα, similar to the form βασίλισα in the Garni Tiridates inscription, and insisted on the spelling parallels between the two inscriptions.

Spellings diverging from the norm, which themselves correspond to evolutions in pronunciation, become ever more common from the second century onwards. Admittedly they do not fit mechanically with chronological evolution, and they usually correspond to the level of education, often linked to the social status of the author of the text42. As will be shown, the Garni inscription was not a royal inscription, which may seem to depreciate script as chronological criterium. But the Aparan one was a royal donation and if the standard of Garni mosaic (located in the royal palace) was higher, it also contained orthographic variants (“misspellings” if one thinks in terms of norms). The fact that this bundle of texts presents spellings similarly diverging from the norm invites us to date them in the late imperial period rather than in the early one, a conclusion that fits with those made on their letter shapes and layout.

3. NAMES

The onomastics of the Garni inscription offer typical evidence on the social life of the circle of people mentioned by the text. But, in addition, one of the names provides crucial chronological information.

Tiridates (Trdat) is a theophoric name that appears frequently in the Parthian aristocracy and in the Arsakid family, especially in its Armenian branch43. It means “Given by Tīr”, the Iranian-Armenian god of writing who was also psychopomp, and who for this reason could be assimilated to Apollon and to Hermes44. The theophoric name Μεννέας refers to the god Men and is typical for Asia Minor45. It is sparsely represented in the other regions of the ancient world. But it has 28 occurrences, or 9.5%, from Western Asia Minor and an enormous amount of 221 ones, or 75%, from Inland Asia Minor46. We have thus every reason to think that the Menneas from Garni came from some eastern province of Roman imperial Asia Minor, in a period when the name had not yet begun to fall out of favor because of Christianization47.

44. Chaumont 1986; Russell 1986.

45. See already Ramsay 1883, 35, for Menneas as theophoric name, on the basis of the information from Pisidia.

46. See LGPN V.B and V.C respectively for Western and Eastern Asia Minor

47. For the fate of Menneas after Christianization, Destephen 2019, 269.

There remains finally the case of the name Martyrios, l. 9, a word that has been first recognized as a personal name by Vinogradov 1990. Vinogradov suggested also that it was not attested only in Christian texts, and to support his claim he adduced the case of an inscription from Ikonion (SEG 15 819, now republished as I.Mus.Konya 183), which he dated to the first half of the third century. He thought that this inscription, which he considered to be a non-Christian text, allowed him to date the Garni inscription, also in a non-Christian context, to the first century CE.

To test the validity of this hypothesis one should start from a survey of the usage of the names Martyrios, Marturis, Martys or Martyria in the various parts of the Empire, on the basis of the LGPN volumes, and from various sources for the regions that are not yet covered by LGPN. The results of this inquiry for the four names can be summarized as follows:

| Source48 | I | II | III.A | III.B | IV | V.A | V.B | V.C | Syr. | Eg. | Total |

| Count | 5 | 4 | 5 | 2 | 5 | 3 | 6 | 9 | 17 | 113 | 169 |

LGPN III.B, from Plataea in Boiotia. On the basis of the first edition of the inscription, LGPN dates a Martyrios to the second or third century CE. He appears in a list of names on a bronze plaque49. The text is dated by its editor to the late second or early third century on the basis of its script and by comparison with a local text of the Diocletianic period, which among others presented curved mu, instead of the M shape of the bronze plaque (which however has besides lunate epsilons, sigmas, and omegas). But, as recalled above, fourth or fifth century inscriptions may also perfectly present such a shape of mu50. The presence in the list of a series of typically Christian names such as Anastasios, Kyriakos and Kyrillos, and of other names that were very popular in the later period such as Simplikios, speaks in favor of a date in the fourth century or later.

50. See above, p. 606.

LGPN III.C., from Ikonion, 2nd c. LGPN: A Futius Aelius Martyris dedicates a funerary monument for himself and his wife Aelia Zoe in the Greek inscription I.Mus.Konya 183 (the document advocated by Vinogradov). The text is engraved on a beautifully decorated marble sarcophagus. The style of the sarcophagus and the script of the inscription point to a date in the third century. The double Roman gentilicium Futius Aelius appears in another Greek dedication of Ikonion made by a woman, Futia Aelia Domnilla, for herself and her husband Aelius Nonius, on another beautiful and richly decorated sarcophagus (I.Mus.Konya 182)51. Given the rare association of the two gentilicia Futius and Aelius and the extreme rarity of the nomen Futius, Domnilla and Martyris were probably closely connected. Both of them belonged to the circle of the traditional Roman elite that was prominent at Ikonion52. It should be observed that Ζώη is not per se a Christian name (it was used already in Hellenistic times, see LGPN s.v.). However, its meaning accommodated well to the Christian faith. Moreover, it was seemingly the name of a Christian martyr of the first half of the second century CE: according to the Christian tradition, the slave couple Ἕσπερος and Ζώη, who lived at Attaleia in Pamphylia, was martyrized in 127 CE, under Hadrian53. As for the name Martyri(o)s, it goes without saying that it fits perfectly well for a Christian. Thus, although, beyond the name Martyris, nothing in the inscription of Ikonion is unambiguously Christian, the couple of Martyris and Zoe might well have been Christian54. The lack of open Christian signature might be explained by the fact that, in this period, it was too dangerous to advertise one’s Christian faith fully publicly, at least in the town of Ikonion itself, and even for people belonging to the traditional elite of the city.

52. Mitchell 1979.

53. Halkin 1957, 245.

54. McLean, I.Mus.Konya 183, interestingly refers to the cross shape of the tau in ταμείῳ, l. 9, but the stroke at the top of the tau is an addition, of which the date cannot be ascertained (see the photo in the ed. pr. Mansel 1954).

Interestingly, another inscription from the region mentions an Aelius Martyrios, the son of Eudromios, who dedicated a funerary inscription, carved on a block, in honor of his deceased brother Eunomios55. The inscription was found at Sadettin Hanı (Zazadin, also Zaz-ed-Din Khan), a site about 27 km north-east of Konya56. The inscription is definitely Christian. As observed by Cronin, not only are the names Eudromios and Eunomios Christian or found in Christian inscriptions, but there is a Christian monogram in the shape of a cross at the beginning of the first line57. For Cronin, the inscription was probably not later than Diocletian and maybe earlier (it is dated to the 4th–5th c. by LGPN). The facsimiles in Cronin’s publication do not make it easy to make an independent judgement. The square shape of the letters could as well be pre- or post-Diocletianic. Besides, the frequency of the name Aelius in the region and the presence or absence of the nomen Futius are sufficient indications to prevent any identification of the Futius Aelius Martyris of Ikonion to the Aelius Martyrios of Sadettin Hanı, the former being besides of higher social standing than the latter. But, indeed, the textual, chronological and geographical proximity between the two inscriptions is a further indication that the Futius Aelius Martyris of Ikonion might have been a Christian, just like his almost namesake of Sadettin Hanı.

56. Cronin 1902, 358–67, nos. 119–39; MAMA VIII nos. 312–24; TIB Galatien 220 (with map of the region); MAMA XI with map p. XXVIII.

57. See Cronin 1902, 362, note 8 on the date of the monogram, comparatively early in the Christian period.

LGPN III.C., from Sienoi, in Pisidia: Martyrios appears as the patronym of the anteirenarches Anatolis in a text that belongs to a group of twenty-nine rock dedications from Kocain Cave, in İndağı, in the Antalya province.58 They were made by eirenarchai, anteirenarchai and diogmitai, the officials in charge of public security in imperial Asia Minor. On the basis of parallel cave locations, it has been suggested that these texts were dedications made to Cybele, although in this case there is no such indication. The religious nature of the texts, if any, cannot be determined. On the basis of the presence of one Aurelius, C. Brélaz dates the text to the third century, while reversing the argument and on the basis of this one Aurelius only H.S. Öztürk prefers to date them before 212: we would be however after the mid-second century, in the context of increasing insecurity in the region (the letter shapes of the Martyrios inscription with its square W-shaped omegas and the spelling διωγμῖτε for διωγμῖται fit with this dating)59. A date in the Severian period, before 212 for most of them, seems likely for this bunch of texts.

59. Brélaz 2005, 374, B85; Özturk 2015, 176 and 179.

To conclude, Martyrios (or Martyris), Martyria and Martys are in overwhelming majority late names from the fourth century onward. For now, not a single name of this series can be securely dated to the first century CE or even to the first half of the second century CE. We have good reason to think that the name began to appear in Christian families in the late second and third century, as suggested by the Sienoi and Ikonion inscriptions, which seem to provide the first cases of the use of the name Martyrios, probably in Christian families.

The script, layout and spelling of the Garni inscription all pointed rather toward a late date. The case of the name Martyrios definitely tips the balance in favor of a late date for this text. It is also a clear indication that in all likelihood the bearer of the name in the Garni inscription was a Christian, which nonetheless, per se, does not make of this text a Christian inscription. However, there remains seemingly a stumbling block against a late dating: the word ΗΛΙΟϹ at the beginning of the inscription.

4. “HELIOS TIRIDATES”

It is no exaggeration to say that the interpretation of the first word has guided most interpretations of the Garni inscription. Interpreting the word as a reference to the Sun god, most scholars have logically attributed the text to Tiridates I60. They however divided about how to make sense of the word.

Trever rejected the view that this was a name qualifying Tiridates and saw here an invocation to the god, “Helios!”61. Indeed, invocations to the god(s), θεοί (only rarely θεός), may be found at the beginning of inscriptions in the Classical and Hellenistic period. Ιnitial invocations of individual gods in the nominative are rare but some are attested. This is the case in a dedication of the city of Kibyra from Puteoli dated to ca. 138 CE, which begins with: [ἀ]γαθῆι τύχηι· Ζεὺς Σω[τὴρ Ὀλύμπιος (?)]62. In this case however, the form of the invocation is made explicit by the association with ἀγαθῆι τύχηι and the layout of the inscription.

62. ΙG XIV 829 (with SEG 53 1090), l. 1.

Other scholars have preferred to see in the Garni inscription a name appended to that of Tiridates, by assimilation of the king to the Sun god63. In this vein, it has even been proposed that Helios concealed the theophoric name Tiran, supposedly redoubling the reference to the god Tīr already present in the theophoric Tiridates, when in fact this god had no connection with the sun64.

64. Manandyan 1951 (on the basis of the conjecture that the grandson of Tiridates III might have been called “Tiran-Trdat”). The hypothesis, already criticized by Trever 1953, 189–190, has however been followed by Sarkisyan 1966, 17–18 (although he thought that the king was Tiridates I); Toumanoff 1986, tab. 13; Hewsen 1978–1979, 105; Muradyan 1981.

In any case, the two interpretations supposed that the king was a devotee of Helios. Indeed, we know that the Sun god, whether he was worshipped as Helios, Shamash, or Mithra, with in addition various other local solar deities, was extremely popular from Iran to Syria and well beyond. A link with the god Helios has thus seemed to exclude the possibility that the king was Tiridates III, the founder of the Christian church of Armenia. Thus, the few scholars who have supported the late date have been at a loss to explain this reference to Helios65. In fact, as observed by G. Wirth, it should not have been a stumbling block against an attribution to Tiridates III, insofar as it was only in the second part of his reign that this king embraced the Christian faith66. But admittedly, this might seem a weak argument. Wirth himself added: “Klarheit über den Helios Tiridates ist vorerst nicht zu gewinnen”67.

66. Wirth 1980–1981, 337, n. 84. This was indeed the view of Hewsen 1985–1986, 32.

67. Wirth 1980–1981, 337, n. 84.

Although they have been quickly pushed back, alternative solutions have been proposed. As early as 1946, Manandyan suggested that the word here stood for the Roman nomen Aelius. He adduced the parallel of the second century Armenian king Pakoros, who in an inscription he set up in Rome after 162 CE, advertised his name as Aurelius Pakoros68. Trever countered the argument by stating that the normal form of the gentilicium in Greek was Αἴλιος, with /αι/, not /η/, “and even more so if it had been in the fourth century, when η was read as ι”69. In 1951, Manandyan himself abandoned his original hypothesis and ever since it has been forgotten.

69. Trever 1949, 22; 1953, 189.

Starting also from the premise that the first name of the inscription was a gentilicium, F. Feydit suggested in 1969 that we have here the name Αὐρήλιος and that the three letters ΑΥΡ had been engraved to the left of ΗΛΙΟϹ, but lost70. This analysis was followed by Chaumont71. Comparing recent, high-quality photos of the stone and that provided by Trever, it appears that the stone has not suffered since the 1950s and that there is no trace of ΑΥΡ (see fig. 2). Furthermore, if indeed the letters ΑΥΡΗΛΙΟϹ had been engraved, the first three letters would not be aligned on the margin, as this is the case in the following lines. Therefore, one can safely conclude with almost all scholars that the restoration [Αὐρ]ήλιος cannot be accepted72. One should read here ΗΛΙΟϹ only.

71. Chaumont 1969, 177–180.

72. J. Reynolds (1971, 152), who first found Feydit’s suggestion attractive for it allowed to move the inscription from the first to the fourth century, abandoned it on the basis of the autopsy and comment of D.R. Wilkinson. However, she added that it might perhaps be that a preceding line, ending with AYP, was cut on a lost block standing above the one we have. But this is an unnecessary assumption. Russell 1986 correctly remarked that the “dimensions of the inscription” do not justify the restoration [Αὐρ]ήλιος.

In fact, Manandyan’s initial hypothesis, ΗΛΙΟϹ for the gentilicium Aelius, can be proved to be correct. The first argument in favor of this solution is that, so great was the prestige of the Empire and so strong were the links with the imperial power, that client kings and other rulers in the dependence of Rome commonly took a Roman gentilicium73. In the Levant, Mesopotamia and beyond, a series of kings or kinglets bore a nomen Romanum.

After 212 almost all Pamyreneans adopted the names Iulius Aurelius, stressing their proximity with the Severan family74. The princes of Palmyra, Odainath, Hairanes, Orodes (as well as their generals) all bear the gentilicium Septimius, both in Greek and Palmyrene inscriptions of Palmyra, and so does Odainath’s wife, the famous Queen Zenobia75. Her son Vaballath was named L. Iulius Aurelius Septimius Vaballathus76.

75. IGLS 17.1 (Palmyra), p. 63–86, no. 54–69.

76. See references in Yon 2002, 294.

The Arabic kings of Osroene (later of Edessa only) also bore Roman imperial gentilicia. Abgar VIII (c. 177/8–212) is known in an inscription and on some of his coins as Septimius Abgar77. One of his descendants, Abgar X, who in 240 was in the second year of his reign, is mentioned as Aelius Septimius Abgar in a Syriac parchment78.

78. Teixidor 1990, doct. A scriptura ext. l. 3. See also Ross 2001, 69–75, and Millar 2006, 211–212.

A king of, or from, Iberia introduces himself as King Fl(avius) Dades in an inscription punched around the edge of the circular base of a silver dish by which he offers the object to one of the grandees of his kingdom79. The inscription was originally dated to the Trajanic period80. Then a date in the third or fourth century was suggested81. The script, the gentilicium Flavius (used as an honorary title) and the context of the find (the dish was found with aurei of Decius and Hostilian of 251) could possibly fit with a Constantinian or post-Constantinian date in the fourth century. But the hypothesis of a reburial of the dish has been proposed, with a much earlier date for the inscription, from the turn of the second-third century onward (the Flavian gentilicium of the king would be inherited from one of his ancestors)82. The question of the chronology of this inscription remains open, but it is certain that this king bore the gentilicium Flavius.

80. Braund 1984, 43.

81. Braund 1993.

82. Linderski 2007 suggests that Dades was not the king of Iberia, but a local kinglet. The pitiaxes Publicius Agrippa (I.Georgien3 235, ll. 2–3) of the mid-second century would provide a parallel.

For Armenia itself, there is the already mentioned case of King Pakoros, who appears in an inscription found in Rome (but lost today) and republished by Moretti as IGUR 415 (I.Estremo Oriente 22). Pakoros bought a sarcophagus for his brother Aurelius Merithates83. Pakoros introduces himself (ll. 2–5) as Αὐρήλιος Πάκορος βασιλεὺς Μεγάλης Ἀρμενίας. A Pakoros known from various literary sources reigned in Armenia in the 160s before being deprived from his kingdom by Lucius Verus84. A king Pakoros appears also in an inscription from the region of Maikop, a dedication on a silver cup, παρὰ βασιλέως Πακόρου (thus without the Roman gentilicium)85. In IGUR 415, Moretti supposed that Pakoros received the gentilicium after he was forced to leave his kingdom and to come to Rome. In fact, there is no necessity to adopt this view, as proved by the fact that the other client kings were fully in charge when they bore their Roman gentilicium. The mention of the Roman gentilicium was probably rather a matter of context (see below for the case of Tiridates also).

84. Fronto Ver. 2.15. On this Pakoros, see the discussion of Moretti IGUR and Van den Hout 1999, 302.

85. I.Estremo Oriente 21. As observed, this Pakoros might well have been the homonymous king of Armenia, but the name was also that of the Parthian king Pakoros II, who reigned between 78 and 110 CE; see above p. 606 with n. 30 and p. 608 with n. 37.

But the case of Pakoros seems however to raise another difficulty. If at an earlier date—supposing that the king of the Garni inscription was not Tiridates I but a later homonym—an Arsakid king of Armenia, Pakoros, had taken the name Aurelius, should not we believe that a later Arsakid Tiridates must also have been an Aurelius? This was one the bases of Feydit’s analysis86. In fact, there is no necessity to suppose a continuity in terms of Roman gentilicium in the Arsakid family of the kings of Armenia. Between Pakoros and Tiridates II or III there is respectively ca. fifty years or more or one hundred fifty. In between, many events may have intervened that might have justified the adoption of a different nomen, which was certainly the case for Tiridates III87.

87. See below on this point.

Admittedly, it remains that if Helius or Helios is frequently used as a cognomen, it is not properly a nomen88. But the point is in fact that Helius or Helios are only alternative forms of the nomen Aelius. An interesting case is provided by the Historia Augusta (2. Aelius), which tells us the life of the father of Lucius Verus, L. Ceionius Commodus. The man was adopted by Hadrian under the name L. Aelius Caesar89. He died in 138 before being able to reign, but, although the details of the story told by the Historia Augusta are largely fictional, it remains certain he indeed took the nomen Aelius. On the coins struck under his name, he is always called L. Aelius Caesar90. However, in his Life in the Historia Augusta most manuscripts spell his name Helius91. It is also the form Helius that appears in the Life of Hadrian (1. Hadrian 23. 12 and 24. 1.) to refer to the same character. The misspelling Helius for L. Aelius Caesar in the Historia Augusta has puzzled modern editors92. The Life of Aelius is dedicated to Diocletian, but just like the rest of the Historia Augusta there remains little doubt that this life was written in the second half of the fourth century93.

89. On the fictional character of this life, see Rohrbacher 2013, 162.

90. RIC2, II. 3, no. 2621–2717 and 2929–2935.

91. See the detail in the apparatus criticus in the ed. Callu et al. 1992. Remarkably, Aelius Spartianus, the “author” of this portion or the Historia Augusta, has also his name spelled Helius in some manuscripts.

92. See the interrogations of D. Magie (1921, 73, n. 1). There is one other case of confusion of Helius for Aelius in the Palatinus mss. for the name of Aelius Maurus, the freedman of Phlegon, himself Hadrian’s freedman (see 10. Septimius Severus 20. 1 with Magie’s note 3 (1921, 418)). The confusion is interesting but cannot be compared with the systematic spelling Helius for L. Aelius Caesar.

93. The debate is masterfully summarized in Rohrbacher 2013.

Another character presents an interesting case, Emperor M. Aurelius Antoninus, better known as Elagabalus, for whom it is worth stressing that no author gives this name (or nickname) before the fourth century94. The name appears under the form Heliogabalus in the Historia Augusta (17. Elagabalus), but also in Eutropius (8. 22), Aurelius Victor (23–24) and the Epitome (23. 2), the common form coming back apparently to an original Kaisergeschichte published in 357 or 358 CE95. It is thus clear that the specific spelling Heliogabalus for the name of Elagabalus, among others in the Historia Augusta, necessarily comes back to the fourth century CE. As for the spelling Helius for the name of L. Aelius Caesar, it appears only in the Historia Augusta but it is perfectly consistent in the Life of the character and is appears also in the Life of Hadrian for the same character. The reason of this choice for L. Aelius Caesar remains unknown but the parallel of the form Heliogabalus invites us to admit that the spelling is not the mistake of some medieval copyist but a deliberate choice of the fourth century writer of this part of the Historia Augusta.

95. Bird 1994, xii–xiii with 116 for the name of the emperor.

These are indeed literary works, not writings of ordinary people. But striking spelling confusions can also be observed as early as the third century for the name of the god Elagabalus, the “God of the mountain”, who was originally venerated at Emesa in Syria and associated to the Sun. The name of the god is most frequently spelled Elagabalus, but sometimes also Helagabalus or Aelagabalus in Latin inscriptions from the Western part of the Empire96.

Admittedly again, these observations all concern Latin texts. Besides, at least as far as Elagabalus is concerned, as a god or as an emperor, it might seem possible to explain the solar-type variations of the names by the solar aspect of the god. However, the analysis would leave unexplained the spelling Helius for Aelius Caesar and the forms Helagabalus/Aelagabalus for the god Elagabalus. The variations can be better explained by phonetic/spelling confusions. They show at least that we should not draw arbitrary barriers between various forms of the same name. In the later period of the Roman Empire there was no watertight separation in Latin between Ael-, El- and Hel-. On the Greek side this time, this is precisely how also it is possible to explain the spelling ΗΛΙΟϹ in the Garni inscription.

As we saw, we have the best reasons to think that Menneas, the stone mason who wrote the Garni inscription (if indeed he wrote the text himself), came from one of the provinces of Eastern Asia Minor. He may have spoken good Greek but, as it was more and more frequent at the end of the imperial period, he did not reach the same standard when it came to writing. As mentioned above, this explains the remarkably consistent series of graphic confusions met in this inscription: αἴκτισεν, αἴτους, αἱ[αυτῷ], λιτουργός, and ματητοῦ. In the late period (fourth-sixth century) can be observed many examples of interchange of ε/αι/η in the inscriptions of Asia Minor, such as it is the case with ε>η: τήκνου, ἐνθάδη, and αι>η: κατάκιντη, κατάκιτη; and conversely η>ε: μέ, σοματοθέκε, and αι>ε: γυνεκί97. In the Egyptian papyri of the Roman period, η frequently interchanges with ι and ει, but also with ε and αι98.

98. Gignac 1976, 235–249, specifically 247–248 for the interchange of αι and η (in both directions), less frequent than the other interchanges, but well attested, however.

For the interchange of αι/η specifically, a good case (the PHI database returns 45 matches) is provided with αι>η in the spellings γυνηκός/γυνηκεί/γυνηκί, with most examples from Asia Minor, beginning as early as the third century CE. Remarkably, several of the texts with this confusion also present a series of both vowel and consonant misspellings, just like the Garni inscription. This is the case for instance for the third century with MAMA VII 221 (Galatia): Αὐρή(λιος) Διογένης ἰδίᾳ | γυνηκύ Αὐρη(λίᾳ) Δόμνῃ | γλυκυτάτη, Αὐρή(λιος) Κυρίων | ἰδίᾳ τυγατρεὶ κὲ Αὐρή(λιοι) τὰ |5 τέκνα εἰδίᾳ μητρεὶ | μνήμης χάριν; and ibid. 284 (Phrygia, Amorion): Αὐρ(ήλιος) | Μενέλαος Ἡλίου | σὺν γυνηκὸς Τατει | μητρὶ Δόμνῃ |5 κὲ ἀδελπῷ Δ̣ιοκλῇ | κὲ Νανᾳ τυγατρὶ | μν[ή]μης κάριν99.

This is probably a similar confusion that was made by Menneas for the gentilicium Αἴλιος. Should we transcribe ΗΛΙΟϹ with or without the aspiration? For those who like Menneas “wrote the way they spoke”, the difference was inexistent, given that the aspiration had been lost for a long time in everyday life pronunciation, and that the pronunciation of the vowels very close or identical. It is also possible that Menneas’ misspelling was facilitated by his knowledge of the correct spelling of the name of the sun. Whether Menneas also saw in the gentilicium an allusion to the god is impossible to decide. An alternative solution would be that, in a process similar to the one that led the author(s) of the Historia Augusta to choose the spelling Heliogabalus for Elagabalus and Helius Caesar for Aelius Caesar, the nomen Aelius of Tiridates was commonly spelt Helius. Between the misspelling by Menneas or the usual and deliberate spelling Helius for Aelius as nomen of Tiridates, only other testimonies could tell us which of these two solutions should be adopted, although in the current state of our evidence the former seems more likely. But the mention of a Roman gentilicium remains certain and this solves once and for all, negatively, the question of the alleged reference to the Sun god in this inscription. We thus transcribe Ἥλιος for the gentilicium Helius/Aelius.

For Tiridates the Great, if we accept Agathangelos’ account, in his youth he was in exile under the protection of a certain Licinius100. The gentilicium of this Licinius is unknown. Maybe (though this should remain a hypothesis) Tiridates adopted the nomen of his protector, given that Aelius was still a frequent Roman gentilicium in third century Asia Minor. Besides, it may seem surprising to observe that while in the second century Pakoros, as Arsakid king of Armenia, had born the gentilicium Aurelius, Tiridates went by Aelius. But we do not know the gentilicium (if any) of the Armenian kings following Pakoros and, as observed, the vicissitudes of Tiridates’ own life may suffice to explain his nomen Aelius. Finally, in the Aparan inscription Tiridates does not have a Roman gentilicium. But the same lack of consistency can perhaps be observed for Pakoros, who bore the gentilicium Aurelius in his inscription of Rome (IGUR 415) but no gentilicium on the silver cup from Maikop (I.Estremo Oriente 21), if indeed it was the Armenian king of that name who was the author of this text101.

101. See above p. 608 with n. 37 and p. 615 with n. 84–85.

We can now be certain that the Garni inscription cannot be dated to the first century CE; that it dates to the late imperial period; and that it mentions a king Tiridates who bore the gentilicium Aelius. In the second part of this article, we offer a reading and restoration of the complete text of the inscription, alongside a discussion of previous readings.

Abbreviations

Epigraphic abbreviations follow those recommended by the AIEGL (URL: >>>> ; accessed on: 01.08.2022). Other abbreviations used:

RIC2 – Abdy, R.A., Mittag, P.F. Roman Imperial Coinage. Vol. II/3. Vespasian to Hadrian (AD 96–138). 2nd ed. London, 2020

RPC online – Roman Provincial Coinage online (URL: >>>> ; accessed on: 01.08.2022)

TIB Galatien – Belke, K. Tabula Imperii Byzantini 4. Galatien und Lykaonien. Wien, 1984

Библиография

- 1. Abramyan, A.G. 1947: [The Greek inscription at Garni]. Etchmiadzin 4/3–4, 61–72.

- 2. Աբրամյան, Ա․Գ․ Գառնիի հունարեն արձանագրությունը․ էջմիածին 4/3–4, 61–72.

- 3. Ananyan, P. 1994: [The Garni Greek inscription]. Bazmavep 152, 111–115.

- 4. Անանյան, Փ․ Գառնիի հունարեն արձանագրությունը․ Բազմավէպ 152, 111–115.

- 5. Arakelyan, B.N. 1956: [Mosaic from Garni]. Vestnik drevney istorii [Journal of Ancient History] 1, 143–156.

- 6. Аракелян, Б.Н. Мозаика из Гарни. ВДИ 1, 143–156.

- 7. Arakelyan, B.N. (ed.) 1951–1976: Garni. I–V. Rezul’taty raskopok [Garni. I–V. Results of the Excavations]. Yerevan.

- 8. Аракелян, Б.Н. (ред.). Гарни. I–V. Результаты раскопок. Ереван.

- 9. Arrizabalaga y Prado, L. 2017: Varian Studies. 3 vol. Newcastle.

- 10. Banaji, J. 2016։ Exploring the Economy of Late Antiquity. Cambridge.

- 11. Bartikyan, H.M. 1965: [The Greek inscription at Garni and Movses Khorenatsi]. Patma-Banasirakan Handes [Historical-Philological Journal] 3, 229–234.

- 12. Բարտիքյան, Հ․Մ․ Գարնիի հունարեն արձանագրությունը և Մովսես Խորենացին. Պատմա-բանասիրական հանդես 3, 229–234.

- 13. Bird, H.W. (ed.) 1994: Liber de Caesaribus of Sextus Aurelius Victor. Liverpool.

- 14. Bivar, A.D.H. 1983: The political history of Iran under the Arsacids. In: E. Yarshater (ed.), The Cambridge History of Iran. Vol. 3/1. The Seleucid, Parthian and Sasanian Periods. Cambridge, 21–99.

- 15. Bobokhyan, A., Gilibert, A., Hnila, P. 2019: The Urartian god Quera and the metamorphosis of the ‘Vishap’ cult. In: P.S. Avetisyan, R. Dan, Y.H. Grekyan (eds.), Over the Mountains and Far Away: Studies in Near Eastern History and Archaeology Presented to Mirjo Salvini on the Occasion of his 80th Birthday. Oxford, 98–105.

- 16. Borschel-Dan, A. 2017: Outside Jerusalem’s Old City, a once-in-a-lifetime find of ancient Greek inscription. The Times of Israel, 23 August 2017 (URL: https://www.timesofisrael.com/once-in-a-lifetime-find-of-ancient-greek-inscription-uncovered-at-jerusalems-old-city-gate/; accessed on: 01.08.2022).

- 17. Braund, D. 1984: Rome and the Friendly King. The Character of the Client Kingship. London–New York.

- 18. Braund, D. 1993: King Flavius Dades. Zeitschrift für Papyrologie und Epigraphik 96, 46–50.

- 19. Braund, D. 1994: Georgia in Antiquity. A History of Colchis and Transcaucasian Iberia, 550 B.C. – A.D. 562. Oxford.

- 20. Brélaz, C. 2005: La sécurité publique en Asie Mineure sous le principat (Ier–IIIème s. ap. J.-C.): institutions municipales et institutions impériales dans l’Orient romain. Basel.

- 21. Brixhe, C. 1987: Essai sur le grec anatolien au début de notre ère. 2nd ed. Nancy.

- 22. Callu, J.-P., Gaden, A., Desbordes, O. (eds.) 1992: Histoire Auguste. T. I/1. Introduction générale. Vies d’Hadrien, Aelius, Antonin. (Collection des Universités de France). Paris.

- 23. Canali DeRossi, F. 2004: Iscrizioni delle Estremo Oriente Greco. Un repertorio. (Inschriften griechischer Städte aus Kleinasien, 65). Bonn.

- 24. Chaumont, M.-L. 1969: Recherches sur l’histoire d’Arménie, de l’avènement des Sassanides à la conversion du royaume. Paris.

- 25. Chaumont, M.-L. 1976: L’Arménie entre Rome et l’Iran I. De l’avènement d’Auguste à l’avènement de Dioclétien. In: H. Temporini (Hrsg.), Aufstieg und Niedergang der römischen Welt II. 9. 1. Berlin–New York, 71–194.

- 26. Chaumont, M.-L. 1986: Armenia and Iran II. The pre-Islamic period. Encyclopaedia Iranica II/4, 418–438. (URL: https://iranicaonline.org/articles/armenia-ii; accessed on: 01.08.2022).

- 27. Cronin, H.S. 1902: First report of a journey in Pisidia, Lycaonia, and Pamphylia. II. Journal of Hellenic Studies 22, 339–376.

- 28. Destephen, S. 2019: Christianisation and local names in Asia Minor: fall and rise in late antiquity. In: R. Parker (ed.), Changing Names. Tradition and Innovation in Ancient Greek Onomastics. (Proceedings of the British Academy, 222). Oxford, 258–276.

- 29. Drijvers, H.J.W. 1980: Cults and Beliefs at Edessa. Leiden.

- 30. Elnitsky, L.A. 1958: [On the epigraphy of Garni and Aparan]. Vestnik drevney istorii [Journal of Ancient History] 1, 146–150.

- 31. Ельницкий, Л.А. К эпиграфике Гарни и Апарана. ВДИ 1, 146–150.

- 32. Eraslan, Ş. 2015: Tethys and Thalassa in Mosaic Art. Art-Sanat 4, 1–13.

- 33. Ferretti, L., Magarditchian, M.A. 2020: Garni. Une inscription grecque convertie en xač‘k‘ar. Revue des Études Arméniennes 39, 215–269.

- 34. Feydit, F. 1969: À propos de Garni. In: P.M. Djanachian (ed.), Armeniaca. Mélanges d’études arméniennes publiés à l’occasion du 250e anniversaire de l’entrée des pères mekhitaristes dans l’Île de Saint Lazare (1717–1967). Venice, 184–189.

- 35. French, D.H. 2012–2016: Roman Roads & Milestones of Asia Minor. (British Institute at Ankara. Electronic Monographs, 1–9). Ankara.

- 36. Garsoïan, N. 1997a: The emergence of Armenia. In: R.G. Hovannisian (ed.), The Armenian People from Ancient to Modern Times. Vol. 1. The Dynastic Periods: From Antiquity to the Fourteenth Century. New York, 37–62.

- 37. Garsoïan, N. 1997b: The Aršakuni dynasty (A.D. 12–[180?]–428). In: R.G. Hovannisian (ed.), The Armenian People from Ancient to Modern Times. Vol. 1. The Dynastic Periods: From Antiquity to the Fourteenth Century. New York, 63–94.

- 38. Gignac, F.T. 1976: A Grammar of the Greek Papyri of the Roman and Byzantine Periods. Vol. 1: Phonology. Milan.

- 39. Halkin, F. 1957: Bibliotheca hagiographica Graeca. 3rd ed. Brussels.

- 40. Hewsen, R.H. 1978–1979:The successors of Tiridates the Great: a contribution to the history of Armenia in the fourth century. In: R.H. Hewsen (ed.), Revue des Etudes Arméniennes 13, 99–126.

- 41. Hewsen, R.H. 1985–1986: In search of Tiridates the Great. Journal of the Society for Armenian Studies 2, 11–49.

- 42. Hewsen, R.H. 1986: Aspects of the reign of Tiridates the Great. In: D. Kouymjian (ed.), Armenian Studies = Études arméniennes: In memoriam Haïg Berbérian. Lisbon, 323–332.

- 43. Hewsen, R.H. 2001: Armenia: A Historical Atlas. Chicago.

- 44. Jennes, G. 2013: The name Helios in Graeco-Roman Egypt. Zeitschrift für Papyrologie und Epigraphik 186, 267–269.

- 45. Kettenhofen, E. 1995: Tirdād und die Inschrift von Paikuli: Kritik der Quellen zur Geschichte Armeniens im späten 3. und frühen 4. Jh. n. Chr. Wiesbaden.

- 46. Khatchadourian, L. 2008: Making nations from the ground up: traditions of classical archaeology in the South Caucasus. American Journal of Archaeology 112/2, 247–278.

- 47. Krkyasharyan, S.M. 1965: [Yet another article about the Greek inscription at Garni]. Patma-Banasirakan Handes [Historical-Philological Journal] 3, 235–238.

- 48. Կրկյաշարյան, Ս․Մ․ Եվս մի անգամ Գառնիի արձանագրության մասին. Պատմա-բանասիրական հանդես 3, 235–238.

- 49. Linderski, J. 2007: How did King Flavius Dades and Pitiaxes Publicius Agrippa acquire their Roman names? In: J. Linderski, Roman Questions II. Selected Papers. Stuttgart, 262–276.

- 50. Lisitsyan, S.D. 1945a: [The Greek inscription of the Garni temple]. Sovetakan Hayastan [Soviet Armenia]. Sept. 23rd, no. 201, 3.

- 51. Լիսիցյան, Ս․Տ․ Գառնիի տաճարի հունարեն արձանագրությունը. Սովետական Հայաստան Sept. 23rd, no. 201, 3.

- 52. Lisitsyan, S.D. 1945b: [Wonderful find]. Kommunist [Communist]. Sept. 30th, no. 207, 3.

- 53. Лисициан, С.Д. Замечательная находка. Коммунист. 30 сентября, № 207, 3.

- 54. Magie, D. 1921: Historia Augusta. Vol. I. (Loeb Classical Library, 139). Cambridge (MA).

- 55. Manandyan, Ya.A. 1946: Gaṛnii hunaren ardzanagrutʻyuně ev Gaṛnii hetʻanosakan tachari kaṛutsʻman zhamanakě / Grecheskaya nadpis’ Garni i vremya postroyki Garniyskogo yazycheskogo khrama [The Greek Inscription at Garni and the Date of the Construction of the Garni Pagan Temple]. Yerevan.

- 56. Манандян, Я.А. Գառնիի հունարեն արձանագրությունը և Գառնիի հեթանոսական տաճարի կառուցման ժամանակը / Греческая надпись Гарни и время постройки Гарнийского языческого храма. Ереван.

- 57. Manandyan, Ya.A. 1951: [New notes on the Greek inscription and pagan temple at Garni]. Izvestiya Akademii Nauk Armyanskoy SSR, Obshchestvennye nauki [Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the Armenia SSR, Social Sciences] 4, 9–35.

- 58. Манандян, Я.А. Новые заметки о греческой надписи и языческом храме Гарни. Известия Академии наук Армянской ССР. Общественные науки 4, 9–35.

- 59. Mango, C.A. 1985: Deux études sur Byzance et la Perse sassanide. I. L’inscription historique de Martyropolis. Travaux et Mémoires du Centre de Recherche d’Histoire et Civilisation Byzantines 9, 91–117.

- 60. Mansel, A.M. 1954: Konya’da bulunan yeni bir Lâhid [A new sarcophagus found in Konya]. Belleten 18, 511–518.

- 61. Maranci, C. 2018: The Art of Armenia. An Introduction. Oxford.

- 62. Marciak, M. 2014: The cultural landscape of Sophene from Hellenistic to Early Byzantine times. Göttinger Forum für Altertumswissenschaft 17, 13–56.

- 63. Mastrocinque, A. 2017: The Mysteries of Mithras: A Different Account. (Orientalische Religionen in der Antike, 24). Tübingen.

- 64. McCrum, M., Woodhead, A.G. 1961: Select Documents of the Principates of the Flavian Emperors, A.D. 68–96. Cambridge.

- 65. Metzger, B.M. 1968: Historical and Literary Studies. Pagan, Jewish and Christian. Grand Rapids (MI).

- 66. Millar, F. 2006: Rome, the Greek World, and the East. Vol. 3. The Greek World, the Jews and the East. Chapel Hill (NC).

- 67. Mitchell, S. 1979: Iconium and Ninica: two double communities in Roman Asia Minor. Historia 28/4, 409–438.

- 68. Moretti, L. 1955: Due note epigrafiche. II. Quattro iscrizione greche dell’Armenia. Athenaeum 33, 37–46.

- 69. Movsisyan, A. 2006: The Writing Culture of Pre-Christian Armenia. Yerevan.

- 70. Muradyan, G.S. 1981: [The Greek inscription of Tiridates I found at Garni]․ Patma-Banasirakan Handes [Historical-Philological Journal] 3, 81–94.

- 71. Мурадян, Г.С. Греческая надпись Трдата I, найденная в Гарни. Պատմա-բանասիրական հանդես [Историко-филологический журнал] 3, 81–94.

- 72. Nersessian, V. 2001: Treasures from the Ark: 1700 Years of Armenian Christian Art. Los Angeles.

- 73. Niehoff-Panagiotidis, J. 2019: Zu der umstrittenen Inschrift aus Silvan/Μαρτυρόπολις. Klio 101/2, 640–678.

- 74. Olbrycht, M.J. 2016: The sacral kingship of the Early Arsacids. Fire cult and kingly glory. Anabasis. Studia Classica et Orientalia 7, 91–106.

- 75. Öztürk, H.S. 2015: Kocain (Antalya) Eirenarkhes, Anteirenarkhes ile Diogmites Yazıtlarının Yeniden Değerlendirilmesi [A re-evaluation of the Kocain (Antalya) eirenarches, anteirenarches and diogmites inscriptions]. Adalya 18, 159–180.

- 76. Perikhanyan, A.G. 1964: [Aramaic inscription from Garni]. Patma-Banasirakan Handes [Historical-Philological Journal] 3, 123–138.

- 77. Периханян, А.Г. Арамейская надпись из Гарни. [Историко-филологический журнал] 3, 123–138.

- 78. Preud’homme, N.J. 2018: On the origin of the Name K‘art‘li: Pitiaxēs Ousas’ intaglio and Karchēdoi Iberians. Iberia – Colchis 14, 212–222.

- 79. Preud’homme, N.J. 2019: Aurelie and Divus Verus – new reading of a Greek inscription from Armazi. Iberia – Colchis 15, 201–213.

- 80. Ramsay, W.M. 1883: The Graeco-Roman civilisation in Pisidia. Journal of Hellenic Studies 4, 23–45.

- 81. Reynolds, J. 1971: Roman inscriptions 1966–1970. Journal of Roman Studies 61, 136–152.

- 82. Robert, J., Robert, L. 1956: Bulletin épigraphique. Revue des Études Grecques 69/324–325, 183–184.

- 83. Rohrbacher, D. 2013: The sources of the Historia Augusta re-examined. Histos 7, 146–180.

- 84. Ross, S.K. 2001: Roman Edessa. Politics and Culture on the Eastern Fringes of the Roman Empire. 114–242 C.E. Rome–New York.

- 85. Rostovtzeff, M.I. 1911: Aparanskaya grecheskaya nadpis’ tsarya Tiridata [The Greek Inscription from Aparan of King Tiridates]. Saint Petersburg.

- 86. Ростовцев, М.И. Апаранская греческая надпись царя Тиридата. Санкт-Петербург.

- 87. Roueché, C. 2004: Aphrodisias in Late Antiquity. The Late Roman and Byzantine Inscriptions. 2nd ed. London.

- 88. Russell, J.R. 1986: Armenia and Iran III. Armenian Religion. Encyclopaedia Iranica II/4, 438–444. (URL: https://iranicaonline.org/articles/armenia-iii; accessed on: 01.08.2022).

- 89. Russell, J.R. 1987: Zoroastrianism in Armenia. Cambridge (MA).

- 90. Salvini, M. 2008: Corpus dei testi Urartei. I. Le iscrizioni su pietra e roccia. Rome

- 91. Sarkisyan, G.Kh. 1956: [About the Garni Greek inscription]. Haykakan SSR Gitutyunneri Akademiayi Teghekagir [Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the Armenia SSR, Social Sciences] 3, 45–56.

- 92. Սարգսյան, Գ․ Գառնիի հունարեն արձանագրության շուրջը․ Հայկական ՍՍՌ Գիտուտյունների Ակադեմիայի Տեղեկագիր 3, 45–56.

- 93. Sarkisyan, G.Kh. 1960: Tigranakert: iz istorii drevnearmyanskikh gorodskikh obshchin [Tigranakert. From the History of Ancient Armenian Urban Communities]. Moscow.

- 94. Саркисян, Г.Х. Тигранакерт: из истории древнеармянских городских общин. Москва.

- 95. Sarkisyan, G.Kh. 1966: [The deification and cult of kings and royal ancestors in ancient Armenia]. Vestnik drevney istorii [Journal of Ancient History] 2, 3–26.

- 96. Саркисян, Г.Х. Обожествление и культ царей и царских предков в древней Армении. ВДИ 2, 3–26.

- 97. Skias, A. 1917: [Inscriptions from Plataea]. Archaiologike Ephemeris 3–4, 157–167.

- 98. Σκιᾶς, Α. Ἐπιγραφαὶ ἐκ Πλαταιῶν. Αρχαιολογική Εφημερίς 3–4, 157–167.

- 99. Stubbs, J.H. 2015: Conserving Greek and Roman architecture. In: C. Marconi (ed.), The Oxford Handbook of Greek and Roman Art and Architecture. Oxford, 455–472.

- 100. Teixidor, J. 1990: Deux documents syriaques du IIIe siècle ap. J.-C., provenant du Moyen Euphrate. Comptes rendus des séances de l’Académie des Inscriptions et Belles-Lettres 134/1, 144–166.

- 101. Thomson, R.W. (ed.) 1976: Agathangelos. History of the Armenians. Albany (NY).

- 102. Thomson, R.W. (ed.) 1978: Moses Khorenatsʻi. History of the Armenians. Cambridge (MA).

- 103. Toumanoff, C. 1986: Arsacids VII. The Arsacid dynasty of Armenia. Encyclopaedia Iranica II/5, 543–546. (URL: https://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/arsacids-vii; accessed on: 01.08.2022).

- 104. Traina, G. 2004: Mythes fondateurs et lieux de mémoire de l’Arménie pré-chrétienne (I). Iran & the Caucasus 8/2, 169–181.

- 105. Trever, K.V. 1949: Nadpis’ o postroenii armyanskoy kreposti Garni [Inscription Relating to the Construction of the Armenian Fortress at Garni]. Leningrad.

- 106. Тревер, К.В. Надпись о построении армянской крепости Гарни. Ленинград.

- 107. Trever, K.V. 1953: Ocherki po istorii kul’tury drevney Armenii (II v. do n.e.–IV v. n.e.) [Essays on the Ηistory of the Culture of Ancient Armenia (2nd Century BCE – 4th Century CE).] Moscow–Leningrad.

- 108. Тревер, К.В. Очерки по истории культуры древней Армении (II в. до н.э.-IV в. н.э.). Москва–Ленинград.

- 109. Van den Hout, M.P.J. 1999: A Commentary on the Letters of M. Cornelius Fronto. Leiden–Boston–Köln.

- 110. Varinlioğlu, E., French, D.H. 1991: Four milestones from Ceramus. Revue des Études Anciennes 93/1–2, 123–137.

- 111. Varinlioğlu, E., French, D.H. 1992: A new milestone from Ceramus. Revue des Études Anciennes 94/3–4, 403–412.

- 112. Vinogradov, Yu.G. 1990: Bulletin épigraphique. Côte septentrionale du Pont, Caucase, Asie Centrale. Revue des Études Grecques 103/492–494, 531–560.

- 113. Weber, U. 2016: Narseh. Encycloaedia Iranica, online ed. (URL: http://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/narseh-sasanian-king; accessed on: 01.08.2022).

- 114. Wirth, G. 1980–1981: Rom, Parther und Sassaniden. Erwägungen zu den Hintergründen eines historischen Wechselverhältnisses. Ancient Society 11–12, 305–348.

- 115. Yon, J.-B. 2002: Les notables de Palmyre. Beirut.

2. Arakelyan et al. 1951–1976. See Khatchadourian 2008 for the history of the first explorations and modern excavations. The exact construction date of the temple is still debated (see Maranci 2018, 26–27, with n. 81). On the symbolic meaning of its modern reconstruction, see Traina 2004, 178–179.